It

had been my intention to use this space to examine the shifts in the employment

of infantry over the course of the war. Envisioning a two-part series to illustrate

these changes, it occurred to me that I had used the word “evolution”, which

describes a gradual approach to change. Two

parts, I found, would be too abrupt to include all the relevant aspects, and as

such I have decided to expand the series: Looking at the ultimate changes in

tactics a little later on while spending some time now on elements of the war

which served as an intermediary between things as they were at the start, and

things at the war’s end.

The

prospect of a long war was becoming more evident as 1915 wore on.

Mutual defenses made for a delicate situation

regarding offensive planning. Only a

large, well coordinated attack on as wide a front as possible could breach the

enemy’s line; but the requisite numbers of trained men and adequate material

support would not be met until med-1916, at least. This left a large amount of time n which to

plan and prepare for such a general offensive, sharing it with the requirement

to prevent or defeat any similar offensive moves on the part of the enemy.

In

December of 1915, command of British forces on the Western Front was

transferred from Sir John French to Sir Douglas Haig. Haig’s despatches, from this point to the end

of the war lend valuable perspective to the overall situation as seen from the

very top. His first such report, dated

19th May 1916 neatly describes the continual effort required to

merely maintain the defensive lines- it “entails constant heavy work. Bad weather and the enemy combine to flood

and destroy trenches….all such damages must be repaired promptly, under fire,

and almost entirely by night.[1] It must be taken into

account that Haig’s despatches (which were publicly released in supplement to

the London Gazette) have a decidedly positive spin.

This

activity certainly occupied the infantry, but it would come at a cost. Using the infantry in laborious tasks might

ensure the men be kept busy, but time spent in this way reduced the amount of

training such a large body of men mostly new to the army (or new to elevated

levels of command) would need for a successful and complex operation that a

decisive counter-attack required. A lack

of this preparation would become painfully obvious at the Somme in 1916.

“At night,” says Professor Tim Cook, “the

once empty battlefield...swarmed with activity.”[2] Even if no major effort to

bring the fight to the enemy might be in progress, it mattered a great deal to

military planners, reliant on accurate information as well as the morale of

individual soldiers to control the battlefield.

There being no foreseeable opportunity for offensive operations for a

period of several months indicated that the infantry would need the ability to

retain a high level of morale and fighting spirit. Holding a static position gave rise to the

use of patrolling and trench raids to keep the men active while concurrently

maintaining pressure against the enemy. Haig goes so far as to note “One form

of minor activity deserves special mention, namely the raids…which are made at

least twice or three times a week against the enemy’s line[3]

To gain perspective of the enemy

defences and overall intentions, patrols would be sent even closer to and

sometimes within opposing trenches. Such

were the importance of patrols that if a compromise needed to be made between

“facilities for observation (and) facilities for protracted resistance”[4]

the latter took precedence if ample efforts could be made for patrolling. “Their

strength may be from two to eight men under a non-commissioned officer.”[5]

Active patrolling taught men how to act independent of larger commands, a

crucial skill to inspire initiative and a good way to educate NCO's and junior

officers who may have to assume control of a battle when attrition rates leave

them senior. Becoming familiar with the ground had great benefits in

planning offensives and would help to raise the men's confidence during

attacks.

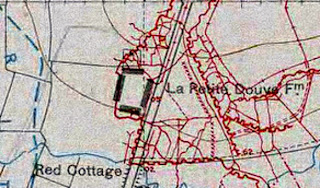

.jpg) Raids differed from patrols. The purpose was not to secure territory, but

to cause a limited amount of damage. They

became the epitome of keeping men at a high level of aggressiveness, and to

keep the enemy off balance and over vigilant.

Trench raids varied in size, from the numbers of a regular patrol to

sometimes that which could be counted as a miniature battle. One of the most successful raids, and one

which would set the template for future operations and secure a peculiar

reputation for Canadians, was conducted early in the war against German

trenches near La Petite Douve Farm in November 1915 by the 7th Battalion, CEF. Raids may well have been opportunistic, but a

great many relied on exacting detail.

The operations order to the Petite Douve raid runs five pages in length

and leaves very little to chance.

Raids differed from patrols. The purpose was not to secure territory, but

to cause a limited amount of damage. They

became the epitome of keeping men at a high level of aggressiveness, and to

keep the enemy off balance and over vigilant.

Trench raids varied in size, from the numbers of a regular patrol to

sometimes that which could be counted as a miniature battle. One of the most successful raids, and one

which would set the template for future operations and secure a peculiar

reputation for Canadians, was conducted early in the war against German

trenches near La Petite Douve Farm in November 1915 by the 7th Battalion, CEF. Raids may well have been opportunistic, but a

great many relied on exacting detail.

The operations order to the Petite Douve raid runs five pages in length

and leaves very little to chance.

The German section of line opposite

the 7th Battalion was a meandering collection of sharp angles; its

shape dictated by geography. For the

most part, their trenches ran generally north-south, parallel to and just west

of a main road. Where a quadrangle of

buildings that was La Petite Douve Farm abutted this road, the German front line

followed its outward edges. Nearly one hundred and fifty yards below the farm,

the Douve River, running approximately west-east,

intersected the road. At this point, the trenches crossed the road

at a right angle and continued along the river’s path, on the northern edge of

the road in an easterly direction. The

raid was to target this particular corner, as it was believed this section

would be easy to isolate for a short period at least. An added bonus would be capturing the machine

gun post believed to be emplaced at the crux of the trench’s angle at river and

road. Battalion commander Lt Col Odlum

set down the number of men to embark upon the raid, and what their specific

jobs would be. Captain L J Thomas was in

overall command of the operation, and he would be headquartered in the forward

Canadian trench with a twenty-three man reserve force to be moved up in case of

heavy resistance. The small group of

men, less than seventy all told going into No Man’s Land were divided into

three groups. Twelve men and an NCO made

up a support team which would occupy a listening post (LP) on the north bank of

the Douve. A covering party, of nine men

and two NCO’s were to protect the makeshift bridges of which there were two

that would enable the assault party to cross.

Four officers, two NCO’s and thirty six men were part of the assault

party. Under the command of Lt A

Wrightson*, theirs would be the difficult task.

On the night of 16-17 November, 1915

the 7th Battalion, according to the operations order, would attack, (with

a concurrent effort of the 5th Battalion) “2 points in the enemy’s

lines opposite its front for the purpose of draining strength & gaining

information concerning his defences.”[6]

Leading up to the operation, artillery fire was expected to cut the German wire

and damage their trenches while trench mortars fired upon Petite Douve Farm

intending to knock out machine gun emplacements there. In the afternoon and evening of the 16th,

rifle fire from the front trenches would be used to keep the enemy fixed in

place, preventing use of communications trenches, with the noise of gunfire

covering the sound of the attacking party moving into their jumping off

positions. Scouts had gone ahead in the

afternoon as a two man patrol “to endeavour to make a daylight report on the

success secured by the artillery in cutting the enemy wire and breaking the

parapet.”[7] With this report, further patrols went out

with bridging ladders to the determined crossing points and placed them there

for the attack team. At eleven o’clock,

the attack team assembled in the forward trenches. Beforehand, they had removed all identifying

information such as id discs, paybooks and uniform insignia. Each man wore a black “veiling mask” to

reduce visibility, and make quick identification possible. It could also be surmised the use of these

masks was to have a psychological element upon the unsuspecting Germans.

H-hour was 11:30 pm. The attack team moved out through gaps cut in

the Canadian wire and traced along the right bank of the Douve, led by the

scouts who had determined the route to the bridging point. Once

in place, the support team took up their positions at the listening post, the

covering team moving over the bridge.

Midnight was when “the assault will be delivered from the bridging

point.”[8] With maximum speed and aggression, the

assault team crossed the river, guided by scouts to the breached wire. The artillery hadn’t been completely successful

and wire cutters were employed to widen the breach. Once in the trench, one group moved down the

length of the trench to the left, clearing their path with hand grenades. At a predetermined point, just beyond the

junction with a communications trench, bales of wire were dropped and men with

shovels went to work to create a barricade. The remainder of this group carried

on down the communication trench to the support line, lobbing grenades the

whole way. Another group had moved right, towards the machine gun position,

taking it by force and setting up a similar block as the one on the left. The

men then made their way into the support trench, meeting up with the team that

had come down the communication trench. Within

minutes, the assault team had effectively taken control of a rectangular

portion of enemy line defined by the bent fire trench at the road, the

communication trench and the length of the support line which ran between the

fire trench and the communication trench.

H-hour was 11:30 pm. The attack team moved out through gaps cut in

the Canadian wire and traced along the right bank of the Douve, led by the

scouts who had determined the route to the bridging point. Once

in place, the support team took up their positions at the listening post, the

covering team moving over the bridge.

Midnight was when “the assault will be delivered from the bridging

point.”[8] With maximum speed and aggression, the

assault team crossed the river, guided by scouts to the breached wire. The artillery hadn’t been completely successful

and wire cutters were employed to widen the breach. Once in the trench, one group moved down the

length of the trench to the left, clearing their path with hand grenades. At a predetermined point, just beyond the

junction with a communications trench, bales of wire were dropped and men with

shovels went to work to create a barricade. The remainder of this group carried

on down the communication trench to the support line, lobbing grenades the

whole way. Another group had moved right, towards the machine gun position,

taking it by force and setting up a similar block as the one on the left. The

men then made their way into the support trench, meeting up with the team that

had come down the communication trench. Within

minutes, the assault team had effectively taken control of a rectangular

portion of enemy line defined by the bent fire trench at the road, the

communication trench and the length of the support line which ran between the

fire trench and the communication trench.

Twelve German prisoners were

manhandled out of the trench and back towards the support team at the LP. While several riflemen kept ready in case of

a sudden counter attack from the direction of Petite Douve Farm, any valuable

information, including the construction and outlay of the trench system was

taken in by the scouts who were moving within the cordoned area. Exactly twenty minutes after the assault team

had made their breach; Lt Wrightson blew one long and three short blasts on his

whistle, to agreed signal to withdraw. The

assault team, again guided by the scouts made their way through the wire,

gathered the bridge party, crossed back to the right bank to rendezvous with

the support team and then back into Canadian lines. A pre-arranged artillery salvo was fired upon

the German line where the assault had taken place. The Germans had put a counter-attack in, but

were too late, the enemy had gone and they were now exposed to heavy fire.

The Petite Douve Raid was a

tremendous success. At the cost of one

man killed and another wounded, the party of men of the 7th

Battalion had struck a fierce blow against a defended line, taken a dozen

prisoners and gained credible intelligence.

It would make the reputation of the battalion, and of the Canadians as

daring “raiders”; which also inspired other Canadian units to mount raids of

their own in a spirit of one-upmanship.

These subsequent raids improved on technique and helped to solidify the

overall esteem of Canadian troops. The

effect of such an operation would be enormous.

It would first inspire confidence in the men taking part of their own

abilities and their leadership. A

successful raid showed them that the enemy could be taken by surprise and kept

the ever crucial fighting spirit at a keen edge. Also, the enemy would be unbalanced, forcing

them to improve their vigilance for such attacks, which wears on physical and

psychological limits; especially if there was a prospect that men in black

masks could drop into a trench at any given time. Information brought back, through prisoners

and the observations of the assault party would go towards the planning of

future operations.

*Lt Wrightson being given command of

the assaulting team is remarkable, considering he is listed as a Private in “D”

Company in the Bn’s nominal role taken upon arrival in England just one year

prior.

[1] Lt Col J H Boraston, ed. “Sir Douglas Haig’s Despatches

(December 1915-April1919)” J L Dent & Sons Ltd. 1919 pg 4

[2] Cook, Tim, “At the Sharp End: Canadians Fighting the

Great War 1914-1916” Penguin Canada, 2007 pg 272

[4] General Staff, War Office, “Field Service Regulations Part

I: Operations” HM Stationary Office, London, 1909 pg 100

[6] Odlum, V W, Lt Col: 7th Battalion CEF

Operation Orders No. 59, 15 November 1915; Appended to Battalion War Diary,

courtesy Library and Archives Canada

No comments:

Post a Comment